EU fines Google $5.2 billion in antitrust probe

The European Union has been on Google's tail for a while now, with a $2.8 billion fine issued in 2017 for anti competitive practises with Google Shopping in search results and now it's back with another. The EU gave Google a record fine, $5.2 billion, over what it says are unfair practices it forces on Android device makers.

The details of how the EU says the company is unfair are a little tricky. Android is an 'open source' operating system that anyone can install on hardware and sell to consumers, but to gain access to Google's 'core' apps, including the Play Store, it requires manufacturers to bundle Google Search along with the Chrome browser and the full suite of "Google apps" on the device.

For phone makers, that means choosing between access to hundreds of millions of Android apps for customers or going it their own way and reinventing the wheel without access to the array of apps that would otherwise come with every Android device.

The apps included in the package are extensive, with everything from Chrome to Google Camera included. Without these apps, Android is barebones: Google provides the OS layer, referred to as 'AOSP' and some apps like SMS with basic functionality, but the rest is left to the manufacturer's imagination.

Essentially, Android without these core apps is not really the Android consumers would come to expect when buying a device advertised as such. Google allows any device maker to install Android for free, since AOSP is open source, but to gain access to the goodness that is the Play Store and Google's superior apps, they must install the whole set and cannot cherry-pick.

Manufacturers can, however, choose to forgo these apps altogether and build their own marketplace, and alternatives, or just use the basic AOSP apps. Nobody is banned from doing this, but saying no to Google's apps means building an ecosystem from the ground up.

This is where Europe takes issue with the arrangement. Manufacturers have been loudly complaining that Google's practices are unfair, because they're blocked from doing deals to further monetize the consumer. For example, some manufacturers have expressed interest in the types of deals where they'd change the default browser bundled with a phone in exchange for cash, or building their own custom flavors of Android with, to give a theoretical example, a SMS app that shows ads.

These practices, under Google's terms, are not allowed. Manufacturers can bundle alternatives, but they can't be set as the default. Europe wants to make Google stop requiring these bundles and let the OEMs cherry pick the bits they want, while leaving out the defaults or choosing to exclude certain apps like Drive.

While I believe that regulation on monopolies is good in many instances, it seems like this law is being broadly applied to benefit manufacturers' bottom line, not consumers. Google's rules came about partially because manufacturers were creating a wild west for Android: they weren't updating their handsets and pre-loaded poorer alternatives to the Google apps that consumers actually wanted.

It's also about the experience. Google created these rules as it saw the mess of Android handsets out there, an inconsistent array of devices with apps that looked different, despite the name 'Android' being used to sell them. By tightening the controls, but still building in the open, Google has been able to wrestle Android into something better and create a friendlier user experience.

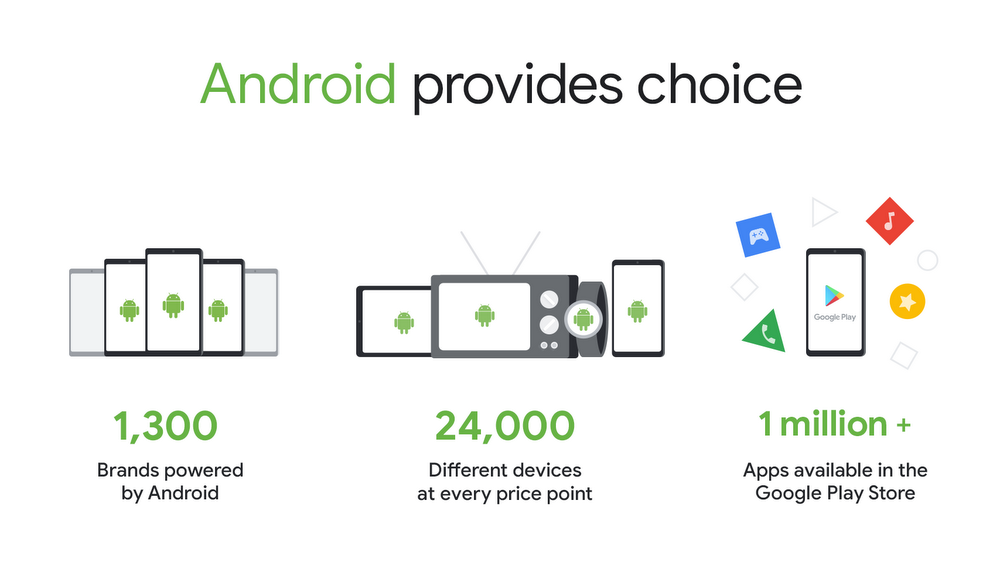

There's also significant holes in the European Union's argument: Amazon's success, and the 24,000 unique devices out there.

If Android's rules are so strict and anti-competitive, why is the most popular Android tablet globally built by Amazon, and ships without the Play Store or core apps? Amazon has successfully built its own custom Android fork, on top of Google's free software, including a marketplace. If the rules were that overbearing, this couldn't happen.

If anything, the European Union's ruling is dangerous, because it'll make it easier for the competition to accelerate. If Google is forced to strip its apps and must instead leave that up to the manufacturers, imagine what the setup experience might be like: download your SMS app, phone app, browser and so on by hand, one by one, when you get a new phone, and uninstall the crappy bundled ones.

This provides Apple with a significant advantage, especially given we have a duopoly in the smartphone software space that means the vacuum left by Google will only benefit one large player that went down the opposite path and hasn't been targeted by antitrust yet.

Thus, the decision shows the weakness in Google's "partially open" strategy vs Apple's fully-closed strategy where users can't even change the defaults, which is more restrictive, but permitted.

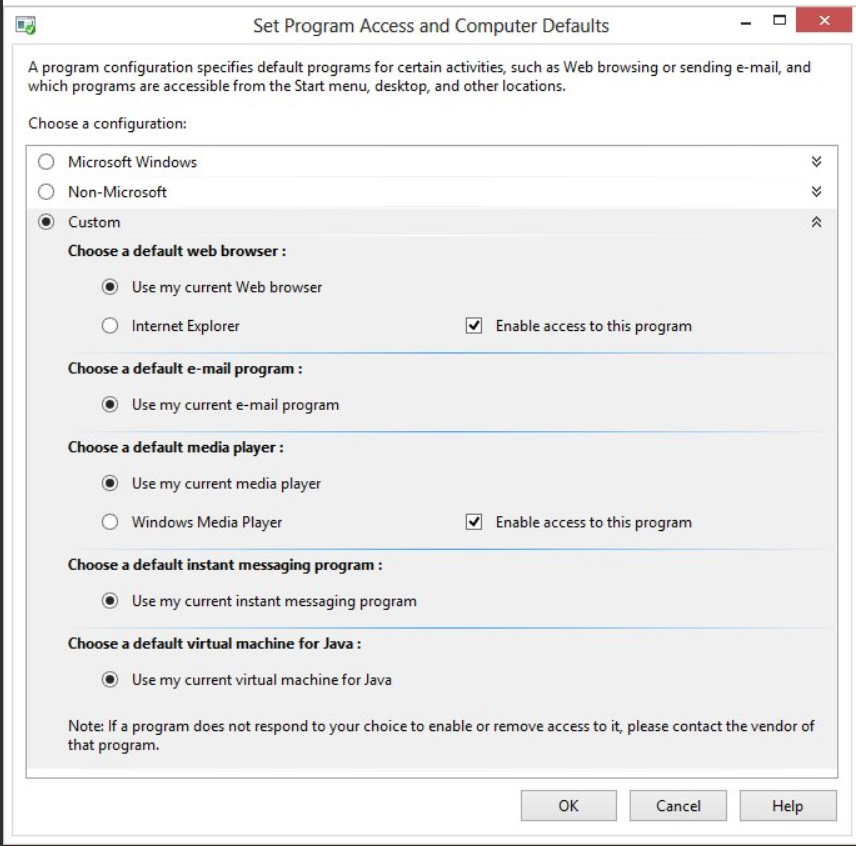

Google's play is similar to the same one that Microsoft used more than two decades ago, bundling a number of basic apps for things like web browsing and media by default, then finding itself also punished by authorities and needing to create this lovely experience:

Google plans to appeal the decision, and it's likely to find some legs with the argument that Android created more choice, not less, even for manufacturers. It's hard to see the net positive here for end users, and if this ruling stands the open-source fundamentals that define Android will fragment into a mess of inconsistent experiences again.

What I'm most curious about is what Google's move is if it loses this case: does Android go closed source? Does it suddenly begin to require large fees from manufacturers to access its ecosystem (a possibility it has raised), or does Google add some sort of awful consent screen, pay the fine, and pretend this didn't happen?

Today, it's difficult to say, but in the coming weeks we're likely to learn that both sides will play hardball, and anything's possible. I'll keep you updated as we learn more, and as understanding of the ripple effects becomes clearer.

Recode interviews Zuckerberg and it's... something

Kara finally got an audience with Mark Zuckerberg and it's interesting reading for a number reasons.

What's clear to see is that he still refuses to take a stance at all on the problems Facebook has with false content, and doesn't believe it's Facebook's prerogative as a platform provider to do so. Worse still, he said that Holocaust deniers are making an honest mistake, so it's probably not a problem for Facebook to solve:

It’s hard to impugn intent and to understand the intent. I just think, as abhorrent as some of those examples are, I think the reality is also that I get things wrong when I speak publicly. I’m sure you do. I’m sure a lot of leaders and public figures we respect do too, and I just don’t think that it is the right thing to say, “We’re going to take someone off the platform if they get things wrong, even multiple times.”

What we will do is we’ll say, “Okay, you have your page, and if you’re not trying to organize harm against someone, or attacking someone, then you can put up that content on your page, even if people might disagree with it or find it offensive.” But that doesn’t mean that we have a responsibility to make it widely distributed in News Feed.

Just hours later he walked back these statements, saying that "I personally find Holocaust denial deeply offensive, and I absolutely didn’t intend to defend the intent of people who deny that." Facebook apparently will take down content that leads to violence... once it happens, but it won't proactively remove it outside of that policy.